On this day—June 23—in 1867, John Ruskin walked into the Grosvenor, a London art gallery—and set in motion the trial at the heart of Falling Rocket. The Grosvenor had opened three months before with the purpose of bringing to the public all that was new and beautiful—and according to its owner, Sir Coutts Lindsay, all that was strange—in contemporary art. At the time considered the country’s foremost art critic, Ruskin had come late to this exhibition, having spent the last few months in Venice obsessed with the Renaissance paintings of Vittore Carpaccio. Just one week before, he had returned to London, clearly intending to resume his role as England’s arbiter of art with a tour of several of London’s galleries.

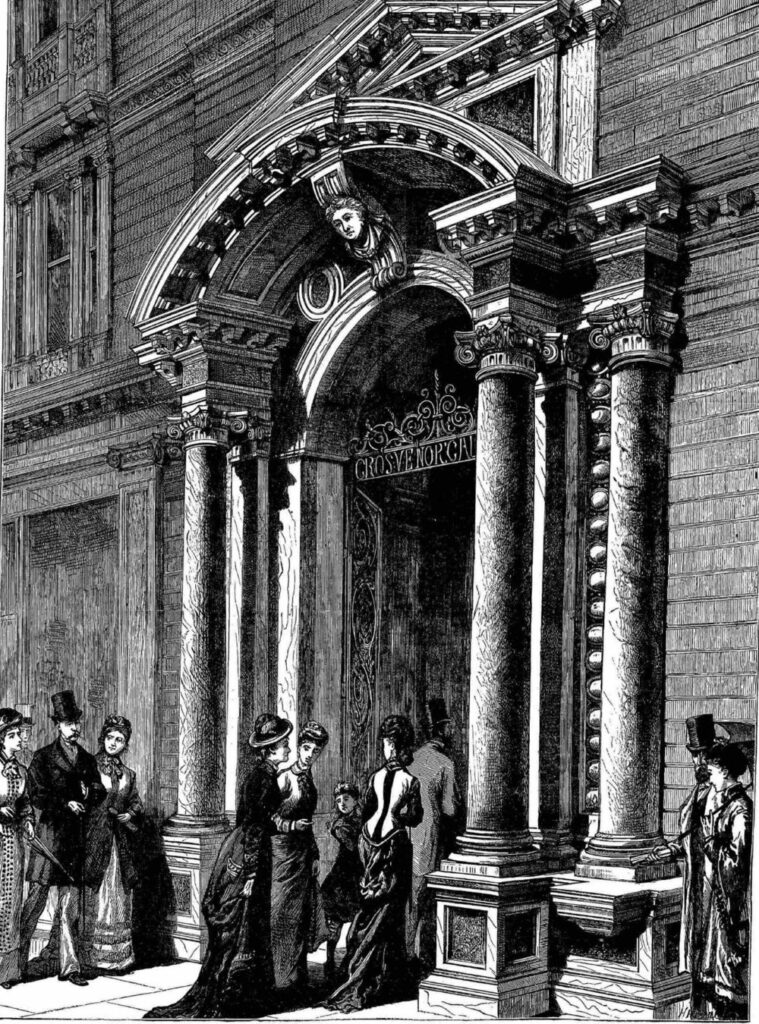

He found disappointment from the beginning to the end of his visit. The very façade of the building (depicted above, from a contemporary print), said to be designed by the great Palladio and salvaged from a Venetian church, must surely have disappointed him: he hated Palladio and all his works. The décor inside he found oppressive. And the art, for the most part, he found indeed strange, and for the most part of little worth—with the works of Edward Burne-Jones a stunning exception. And the seven dark works of James Whistler he considered the worst of all. Within days, Ruskin had composed an attack on the Grosvenor and upon Whistler, which provoked Whistler into suing him. Nearly a year and a half later, this would lead to the celebrated trial Whistler v. Ruskin.

In Falling Rocket, I offered up a summary of Ruskin’s remarks about the Grosvenor, with particular attention to his blast at Whistler. Below is Ruskin’s record of his visit in full.

I must not close this letter without noting some of the deeper causes which may influence the success of an effort made this year in London, and in many respects on sound principles, for the promulgation of Art-knowledge; the opening, namely, of the Grosvenor Gallery.

In the first place, it has been planned and is directed by a gentleman in the true desire to help the artists and better the art of his country:—not as a commercial speculation. Since in this main condition it is right, I hope success for it; but in very many secondary matters it must be set on different footing before its success can be sure.

Sir Coutts Lindsay is at present an amateur both in art and shopkeeping. He must take up either one or the other business, if he would prosper in either. If he intends to manage the Grosvenor Gallery rightly, he must not put his own works in it until he can answer for their quality: if he means to be painter, he must not at present superintend the erection of public buildings, or amuse himself with their decoration by china and upholstery. The upholstery of the Grosvenor Gallery is poor in itself; and very grievously injurious to the best pictures it contains, while its glitter is as unjustly veils the vulgarity of the worst.

In the second place, it is unadvisable to group the works of each artist together. The most original of painters repeat themselves in favourite dexterities,—the excellent of painters forget themselves in habitual errors: and it is unwise to exhibit in too close sequence the monotony of their virtues, and the obstinacy of their faults. In some cases, of course, the pieces of intended series illustrate and enhance each other’s beauty,—as notably the Gainsborough royal Portraits last year; and the really beautiful ones of three sisters, by Millais, in this gallery. But in general it is better that each painter should, in fitting places, take his occasional part in the pleasantness of the picture-concert, than at once run through all his pieces, and retire.

In the third place, the pictures of scholars ought not to be exhibited together with those of their masters; more especially in cases where a school is so distinct as that founded by Mr. Burne-Jones, and contains many elements definitely antagonistic to the general tendencies of public feeling. Much that is noble in the expression of an individual mind, becomes contemptible as the badge of a party; and although nothing is more beautiful or necessary in the youth of a painter than his affection and submission to his teacher, his own work, during the stage of subservience, should never be exhibited where the master’s may be either confused by the frequency, or disgraced by the fallacy, of its echo.

Of the estimate which should be formed of Mr. Jones’s own work, I have never, until now, felt it my duty to speak; partly because I knew that persons who disliked it were incapable of being taught better; and partly because I could not myself wholly determine how far the qualities which are to many persons so repulsive, were indeed reprehensible.

His work, first, is simply the only art-work at present produced in England which will be received by the future as ‘classic’ in its kind,—the best that has been, or could be. I think these portraits by Millais may be immortal (if the colour is firm), but only in such subordinate relation to Gainsborough and Velasquez, as Bonifazio, for instance, to Titian. But the action of imagination of the highest power in Burne-Jones, under the conditions of scholarship, of social beauty, and of social distress, which necessarily aid, thwart, and colour it, in the nineteenth century, are alone in art,—unrivalled in their kind; and I know that these will be immortal, as the best things the mid-nineteenth century in England could do, in such true relations as it had, through all confusion, retained with the paternal and everlasting Art of the world.

Secondly. Their faults are, so far as I can see, inherent in them as the shadow of their virtues;—not consequent on any error which we should be wise in regretting, or just in reproving. With men of consummately powerful imagination, the question is always, between finishing one conception, or partly seizing and suggesting three or four: and among all the great inventors, Botticelli is the only one who never allowed conception to interfere with completion. All the others,—Giotto, Masaccio, Luini, Tintoret, and Turner, permit themselves continually in slightness; and the resulting conditions of execution out, I think, in every case to be received as the best possible, under the given conditions of imaginative force. To require that any one of these Days of Creation should not have been finished as Bellini or Carpaccio would have finished it, is simply to require that the other Days should not have been begun.

Lastly, the mannerisms and errors of these pictures, whatever may be their extent, are never affected or indolent. The work is natural to the painter, however strange to us; and it is wrought with utmost conscience of care, however far, to his own or our desire, the result may yet be incomplete. Scarcely so much can be said for any other pictures of the modern schools: their eccentricities are almost always in some degree forced; and their imperfections gratuitously, if not impertinently, indulged. For Mr. Whistler’s own sake, no less than for the protection of the purchaser, Sir Coutts Lindsay ought not to have admitted works into the gallery in which the ill-educated conceit of the artist so nearly approached the aspect of wilful imposture. I have seen, and heard, much of Cockney impudence before now; but never expected to hear a coxcomb ask two hundred guineas for flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face.

Among the minor works carefully and honourably finished in this gallery, M. Heilbuth’s are far the best, but I think M. Tissot’s require especial notice, because their dexterity and brilliancy are apt to make the spectator forget their conscientiousness. Most of them are, unhappily, mere coloured photographs of vulgar society; but the ‘Strength of Will,’ though sorely injured by two subordinate figures, makes me think the painter capable, if he would obey his graver thoughts, of doing much that would, with real benefit, occupy the attention of that part of the French and English public whose fancy is at present caught only by Gustave Doré. The rock landscape by Millais has also been carefully wrought, but with exaggeration of the ligneous look of the rocks. Its colour as a picture, and the sense it conveys of the real beauty of the scene, are both grievously weakened by the white sky; already noticed as one of the characteristic errors of recent landscape. But the spectator may still gather from them some conception of what this great painter might have done, had he remained faithful to the principles of his school when he first led its onset. Time was, he could have painted every herb of the rock, and every wave of the stream, with the precision of Van-Eyck, and the lustre of Titian.

And such animals as he drew,—for perfectness and ease of action, and expression of whatever in them had part in the power of the peace of humanity! He could have painted the red deer of the moor, and the lamb of the fold, as never many did yet in this world. You will never know what you have lost in him.