Since the release of Falling Rocket last semester, a couple readers have come to me with a….well, with a plaint, if not quite a complaint. I obviously write about many paintings by James Whistler in the book—but I only provide illustrations of a few of them. They wanted more. And I would have loved to have given them more. But providing that many illustrations, of a reasonable quality and in full color, would have broken the bank of my publisher.

Given that limitation, I recommend that every reader of the book bookmark and take advantage of the best collection of Whistler’s paintings online: a fully comprehensive set, of admirable quality, very fully annotated, and presented entirely without advertising: The Painting of James McNeill Whistler: a Catalogue Raisonné, at https://whistlerpaintings.gla.ac.uk/catalogue/.

Since I could not include illustrations of more than a few of Whistler’s great works in Falling Rocket, I thought that instead, I might here from time to time present a few of those I consider the very best.

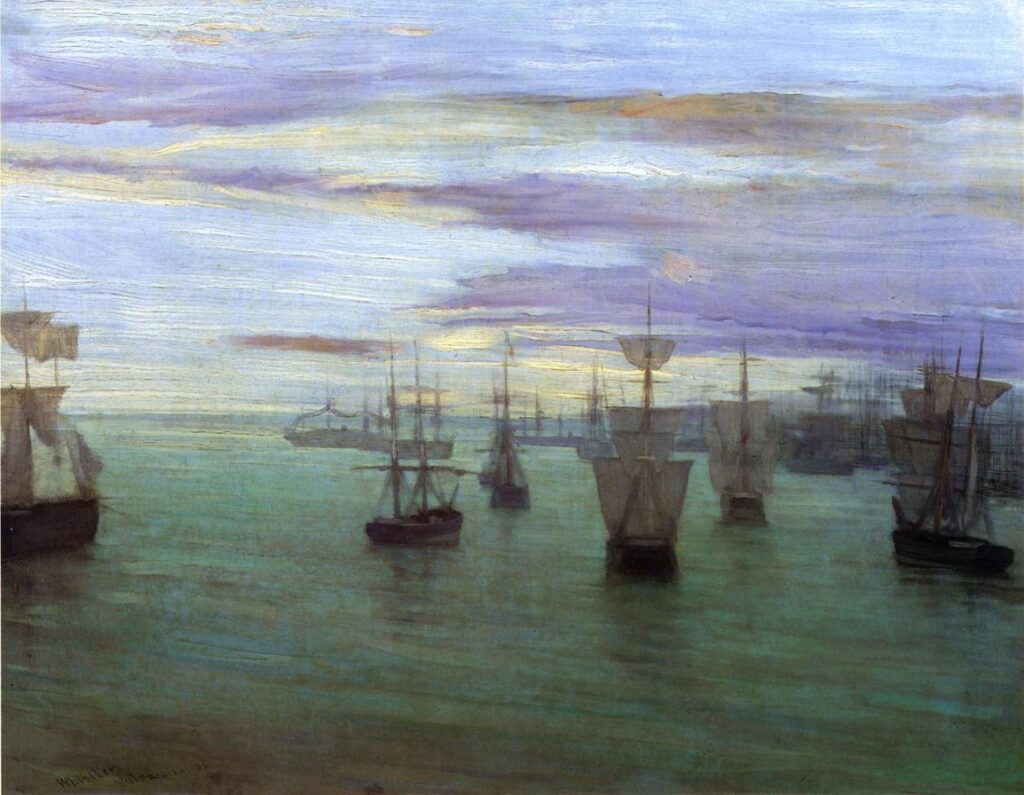

And so, above, you’ll find one of them: Whistler’s Crepuscule in Flesh Colour and Green: Valparaiso. Whistler painted this one in 1866, in the midst of a fool’s errand: a voyage to Chile as the advance guard for a gang of mercenaries commissioned with bringing torpedoes there intended to sink a few warships from Spain, which was then at war with Chile. (That war ended, however, before the torpedoes arrived, and the mission came to nothing.) This meant that Whistler in Valparaiso had little to do besides eavesdropping on the natives, smoking the local cigars, and apparently sleeping with his only companion on the mission—his commander’s wife. And, he painted.

Two of Whistler’s Valparaiso paintings anticipate many great works that were to come. With his Nocturne in Blue and Gold: Valparaiso Bay in particular, he produced his very first nocturne. It was far from his best one, to my mind, with its botched perspective, its jarring focus upon the vertical rather than the horizontal, its confusion rather than the typical quiescence of the nocturnes to come. Far superior to this nocturne, in composition and in effect, is his Crepuscule, which in the domination of its near-horizontal masses of cloud, sky, and ocean anticipates the technique if not the tone of the later nocturnes. In tone, this work stands alone: depicting dusk allows him to work out a true symphony of color, paradoxically brilliant and yet muted, fitting for this evocation of utter tranquility in the midst of war.

Crepuscule in Flesh Colour and Green somehow ended up in the possession of Whistler’s factotum-friend become enemy Charles Augustus Howell. Howell died in 1890, and at the auction that followed the Crepuscule was bought by W. Graham Robertson who fifty years later donated it to the Tate Gallery—now the Tate Britain. While that is where the painting is today, anyone hoping to see it—see it, perhaps in the company of the Tate’s other great Whistler, his Nocturne: Blue and Gold—Old Battersea Bridge—would however be disappointed. For the Tate has, for some inexplicable reason, chosen not to put the Crepuscule on display.

Here’s hoping that they change their minds—and soon.