Arrangement in Grey and Black: Portrait of the Painter’s Mother, contains what is arguably the most instantly-recognizable and iconic pose in all of American art. But when Whistler set out to paint his mother Anna, he had a very different conception for the portrait in mind. Had he not taken pity upon his mother and restructured the painting completely, the painting that has given him global fame would never have come about.

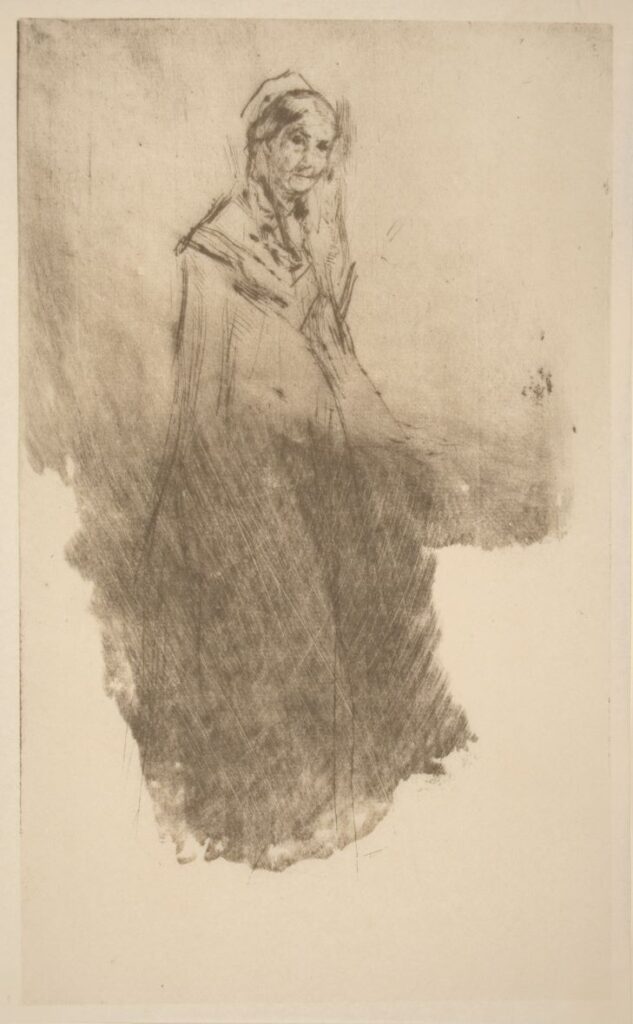

When in the summer of 1871, left in the lurch by a model who had tired of his grueling sessions and quit, he turned to Anna and exclaimed “Mother, I want you to stand for me!” Standing for him, not sitting, was what he had in mind. And the prospect of standing for him made her uneasy. “I am not as well then as I am now,” she wrote to a friend three months later, but not wanting to bother her son by complaining, she agreed. How Whistler posed her cannot be known exactly, for no canvas from those sessions survive. But the etching above that he made of his mother at around this time—and quite likely exactly at this time—suggests that he planned a conventional three-quarter, full-length view of her.

Anna’s unease was certainly warranted. Her son was notorious for the harshness with which he treated his sitters (or his standers), demanding that they remain frozen in position for hours on end, often for dozens of sessions. Many of those who modeled for him later attested to the distress that it caused them. 8-year-old Cecily Alexander, the subject of one of his finest portraits, spent fully seventy sessions, as she later termed it, as his “victim”: “I used to get very tired and cross, and often finished the day in tears.” And Whistler’s demands upon 73-year-old Henry Cole were enough to kill him—or at least the artist Walter Sickert thought they were. Having put the old man, posing in evening dress and a heavy cloak, through many sessions, Whistler continued even after Cole became ill. On April 17, 1882, he painted Cole for an hour and a half while, Cole complained to his son, he “merely touched the light on his shoes.” The next day, Cole died.

Anxious but uncomplaining, then, Anna Whistler began her sessions standing “as a statue,” and she suffered. But after two or three sessions Whistler could not ignore mother’s strain and relented, agreeing to paint her sitting, instead. He set her in a straight-backed chair, perpendicular to the viewer and flush against the grey wall of his studio. He propped up her feet on a footstool. And then he painted her, Anna remembered, perfectly at my ease,” and with a confidence that, until then, Whistler feared he had lost. By October he had his icon: the painting that would, by its eventual enshrinement in the Louvre, confer upon him artistic immortality.

Arrangement in Grey and Black, then, is a perfect argument against

sticking to one’s original intentions.