November 29, 1878—this day 146 years ago—was, for James Whistler and John Ruskin both, a day of taking stock. For this was the day after the verdict in the great case of Whistler v. Ruskin.

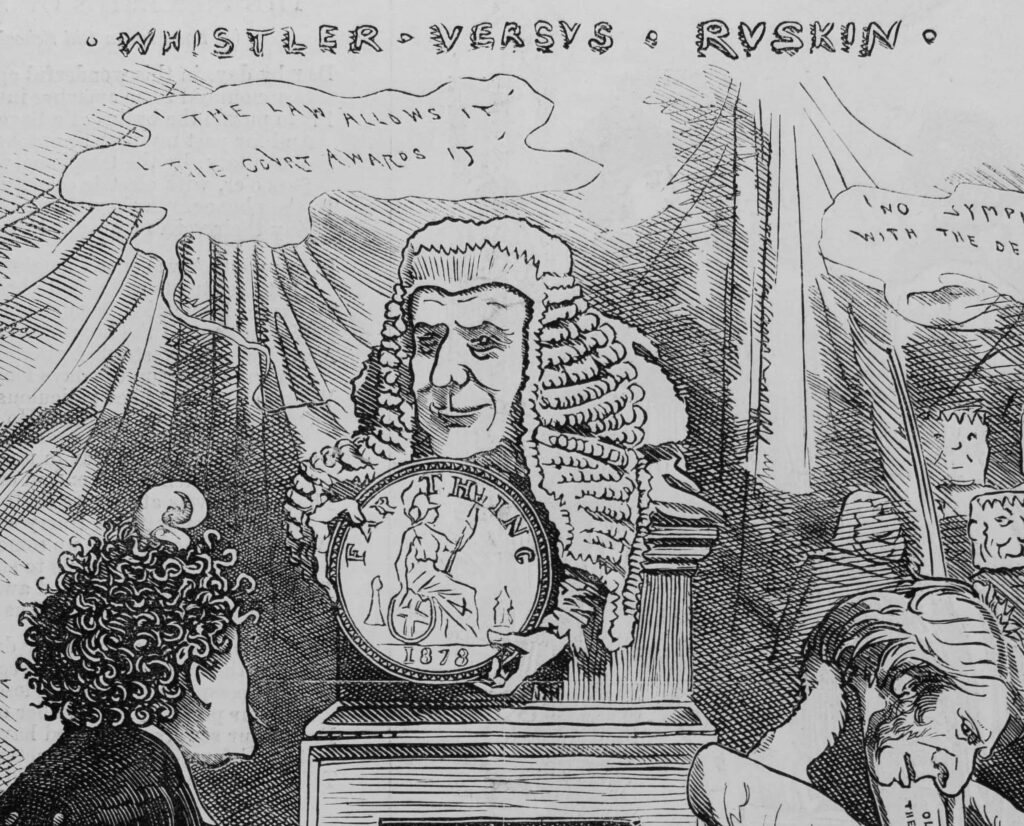

Whistler had in the courtroom the day before exuberantly proclaimed victory, shouting across the courtroom to a friend and reporter “it’s a great triumph!” And for him this day was on to was one to bask in it. But while he might have succeeded in convincing himself that the world–or at least all who mattered in the world–considered his triumph as absolute as he did, in reality it was only in his own mind had he come out of the trial the absolute winner. “I came home,” he wrote to his solicitor, “to find my table strewn with letters of congratulation and sympathy.” But a look at the several letters that came to him in the wake of the trial shows a great deal of sympathy–and precious little congratulation. And though in the days and years after the trial he showed a great deal of joy in the farthing he gained from the verdict, he surely realized that the debt he had incurred from the trial, added to the massive debt he had already built up, had made his eventual insolvency inevitable. Any victory he had earned carried with it the promise of a great loss.

For John Ruskin, learning of the verdict on this day while in seclusion at his Coniston home, the farthing damages of the verdict might signal to the world that his loss was insignificant, or not even a loss at all. But to him the insignificant damages meant nothing. For him, the verdict meant a crushing loss: a denial of his hitherto-unquestionable authority as Britain’s arbiter of art. He would sulk on this day, and on the next would take steps to remove himself from that public, writing not one but two letters of resignation from his professorship at Oxford. “I cannot hold a Chair from which I have no power of expressing judgment without being taxed for it by British Law,” he complained.

For Whistler, then, triumph; for Ruskin, defeat. But this day marked not simply the end of one struggle, the struggle in the courtroom. It marked as well the beginning of another—a lifelong one for both men. For Whistler, who’s art sold no better after Whistler v. Ruskin than it had before, his fight to gain public acceptance of his art had just begun, and would continue until the day he died. For Ruskin, his need to recapture the confidence of the public, and regain his authority as a great Victorian sage and prophet, would continue for another dozen years and more, until the fog of mental decline consumed him. In this way, as I have said before, Whistler v. Ruskin became the battle of two lifetimes.